Foreword

This page is exceptionally dense… to summarise, we want to design the most sustainable projects we can and are concerned that our built environment does not reveal the true scale of that challenge. We are looking for ways to help address that problem, and that is the whole message here. You do not need to read further.

If you do wish to read further, understand that this page is not a marketing tool. We are not trying to sell you anything here, instead we wish to talk openly about the problems we see and engage in a conversation about how we respond. This page harkens back to an earlier time when Architects would use writing like this as a tool to both solidify their own thought process and formulate a suitable response to complex problems, so is better interpreted as a log book, or journal. This is a problem solving and creative tool that very deliberately smashes a range of seemingly scattered concepts together in order to help synthesise new ideas, and it is through the act of writing itself that these ideas are given the space they need to evolve into a proper response. The value of the below texts is that they carry explanatory power for the images we show you in our gallery. Those images are the end product, whereas what we’re doing here is exposing the thought processes that led to them, revealing the missing bits of information needed to interpret why they look the way they do.

In short, our philosophy is to fuse simplicity and the finding of beauty in imperfection and change, with an empirical, experiential and evidence-based understanding of our world. This leads to an architecture that attempts to be more fluid or probabilistic in the face of contextual change.

Mobilis in Mobili

There’s a great line in an incredibly dusty book called Novum Organum we like…

‘...human understanding is, by its own nature, prone to abstraction, and supposes that which is fluctuating to be fixed’.

A great place to start as it sets the tone of the ideas we want to explore in this text. Bacon is trying to tell us that the human mind, as great as it is, naturally tends toward a misinterpretation of the world through implicit biases, and this tendency if not recognised and addressed through suitable mechanisms can lead us astray in our understanding and decision making. The ideas he then goes on to unravel throughout his book gave us a looking glass into a different world, one that became the foundation of a more empirical way of seeing.

If we were to define the closest philosophy that Deo ascribes to, or at least aspires toward, we’d probably borrow from the Japanese a little. There are a set of ideas combined within the term Wabi Sabi which we value greatly, a philosophy which finds beauty in the simple and the imperfect. It is a collection of concepts that acknowledge the natural world we live in is one of change, and carries with it its own aesthetic by result; a pattern of no pattern which sets it apart from the objects humanity ordinarily puts into the world. It requires a subtle shift in perspective, valuing tolerance, asking us instead to find beauty in entropy, in the passage of time, in a continual change of state. Is this a purely Japanese concept? We’d argue no, we can go back in time to Heraclitus and his famous maxim ‘everything flows’ to find a roughly similar idea, that everything is always in this state of becoming something else and it is ever our role to find a way to navigate those waters.

If you were to take these two ideas and sort of rub them together provocatively, perhaps to some suitably chosen mood music, the resulting estranged lovechild you’d arrive at is close to where we at Deo try to position ourselves, though we find it a difficult concept to describe. It’s like trying to fuse two different types of mechanical mathematics, one classical vs. one statistical, one deterministic vs. one probabilistic, one solid vs. one a bit fluffy, both within a wider language that is geometrically bound and contextual, like sitting in the shadow of something we cannot directly see but impacts us all the same. Frowning, you might say this is something of a strange position to be taking right? It clearly makes things a lot harder than they need to be, so why do this at all? To that we’d say, you’re absolutely right, but it is the ideas themselves which interest us and there is at least some method to the madness here to find, so we’d like to take the opportunity (if you’ll kindly grant us the time) to talk it all through, and hopefully there will be some things of interest for you to go away with by the end.

It is in the nature of being an Architect that we spend our days navigating often contradictory forces. Our built environment is complex, people equally so, we live in a maze of expectation and regulation which rarely can be reconciled simply and it is this complexity that often tempts us to bias toward safer, more well-trodden paths. We understand this, we even empathise, most of us want a quiet life, and there are certainly some things -like fire protection- you really don’t want to be messing around with, but the question we’d put forward is what if these ‘safer paths’ aren't, in reality, all that safe? It’s an interesting question; if you’ve established a series of reproducible forms or processes which serve their purpose well within one context, what happens when the context changes? Do we change too, or can we instead say with confidence it doesn’t matter? This is the really big question which keeps us up at night, the one we ask ourselves often. If architecture forms the background world to our lives, the playground of reaction you might call it, and we define that context mostly as we see fit, then could we not also say it carries the power to be selective, to frame our perception of things? What happens when a process self-selects to only show us the things we want to see, avoiding the things we don’t… or perhaps worse, shows us solutions which actually aren’t solutions at all or that miss the point entirely? Well… then we’d argue we’d have a problem, and be in very real danger that over time things could get quite desperate indeed.

In 2008 NASA decided to sit down and use their knowledge of planetary dynamics to work out where we needed to be to keep the Earth’s complex dynamic planetary system stable. The process itself is unimportant here, if you’re interested the Met Office do some great guides, what’s important is that they defined the CO₂ levels for the whole planet as needing to hit a target ‘no greater than 350PPM’ (parts per million), and ‘ideally a good amount less’.

At the time of writing, the current measured CO₂ level is sitting somewhere around 430PPM’ish, which when multiplied into the 5.14 quadrillion tonnes of atmosphere this planet has, gives us a number roughly around the 625 billion tonnes of CO₂ mark over where we need to be. For context, a large proportion of the world’s population is fed on rice as a staple every day and we don’t even produce a billion tonnes of that per year. The CO₂ needing to be removed from our atmosphere to hit the 350PPM target is the equivalent of around seven hundred years of rice growth to feed populations worldwide.

This is a significant figure, but sadly also probably falls a little short. The oceans have been kindly absorbing about 25-30% of the CO₂ we’ve been creating for a very long time, converting it to carbonic acid and changing the pH levels in the process (another serious problem in itself). If the oceans start outgassing CO₂ as we reduce the wider CO₂ levels in the atmosphere (as some far smarter people than us are concerned that they will), then we’ll likely find ourselves needing to take significantly more than this from the atmosphere, so making an already huge problem, very much worse.

When did we pass this threshold?... the answer is circa 1986; we’ve been measuring CO₂ levels for quite some time, this is what the empirical data shows. At the time when Carl Sagan was sitting in the American Congress describing clearly and simply the mechanisms and impacts of global warming, plus adding his measured concerns we’d be leaving an impossible problem for future generations to solve if we chose not to act, was also roughly around the same time when the situation started becoming an issue. For each year that has passed beyond this 1986 threshold, the overall cost of fixing the problem has progressively increased. Not only must we build exactly the same infrastructure and make the same societal changes that would have been necessary back in 1986 to fix the problem (i.e. upgrading our energy generation systems) but we must now also do so for a larger population, with greater demands, and with the additional need to remove the CO₂ we’ve already introduced on top (in addition to repairing any collateral damage caused in the meantime).

This is our hard reality, and it is a reality narrated by the choices of a single generation.

In 2018, the pre-AR6 IPCC Special Report identified that the last date by which significant societal changes needed to start being implemented -at pace- to prevent severe climate disruption was 2020 [without relying on overshoot]. We are writing this in 2025, five years beyond this cutoff date [and the last date given to peak CO₂ production if we do rely on overshoot]. By current data at time of writing, there has been no measurable slowdown in CO₂ production… nor any other greenhouse gas for that matter. The good news is that renewables are being installed at the fastest pace they’ve ever been… the less good news is that mostly this increase is avoiding only the need to burn even more fossil carbon than we otherwise would be, so is replacing expansion rather than base generation. Whilst it is true the UK has indeed managed to reach about 50% mix of low carbon renewables and nuclear, we’d point out this is only to the current electrical grid size, roughly 330TWh (terawatt hours) per annum. We have yet to start making any truly significant strides toward a low-carbon, mostly electricity-based society en masse, and when we do, it will multiply the grid demand somewhere between two to five times where it currently stands (depending on how well we upgrade our infrastructure and buildings and what processes we adopt for manufacture and agriculture), which means in reality, we are currently nowhere near close to where we need to be.

It is also important to add that we’re only talking about CO₂ here, we’ve not even started talking about the wider impacts of this change, i.e. biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, AMOC changes, weather and cloud patterns, acidification and deoxygenation of the oceans, microplastics and forever chemicals, ice melt and albedo change, deforestation or any of the other indicators we could bring to the table… all of these are talked through in far more detail by other sources, but they all mostly sum to the same observation; the situation is serious and the hour is getting late, and in all honesty, when trying to talk about them openly it’s hard to avoid sounding close to hyperbolic; the challenge of fixing everything dwarfs in scale anything else humanity has ever tried to do, we’re ultimately attempting to terraform a planet as sci-fi as that may sound, and we shouldn’t underestimate how big a task that actually is. Can we do it?... maybe… we choose to believe that we can, we got ourselves into this mess, and we believe we can dig ourselves back out, and there’s a lot of great work being done by good people which gives us reason for hope, but we don’t see a clear path to achieving these goals if we keep following the same familiar paths we’ve chosen to date. Our professional obligations demand that we find answers, and we know the implementation of those answers means that sooner or later we’re going to need to change course significantly; that appears unavoidable at this stage. The alternative is that changes will be forced upon us irrespective of what we may or may not wish, and they probably aren’t going to be good. As Feynman warned, ‘you do not argue with nature’.

There’s a great deal more we could say here but we’re trying to keep things brief; there are additional discussions within wider climate circles telling us inertia within the climate system may not be as big a problem as implied by the targets above, meaning if we can reduce our emissions quickly the climate system will respond equally quickly. Conversely there are other discussions which suggest the earth energy imbalance is now much larger than anticipated due to recent reductions in cloud seeding particulates and atmospheric sulphur dioxide, meaning the IPCC’s predictions for the rate of heating and future temperatures may be too optimistic, temperature changes instead may be accelerating. We’ve tried to sit in the middle ground here relying on Met Office, Copernicus, IPCC, NOAA and NASA information, and hopefully this is enough for you to start seeing the game we’re going to play over the next few blog posts. Trying to understand the why of what we’re doing is all about accepting our shared context, it is an argument for change in place of staying where we feel safe and will likely get a fair bit more complicated before we can distil the concepts we want to talk through.

Navigating our rapidly changing physical reality requires that shared understanding of truth, that was the essence of Bacon’s life work. Now however we’re finding those foundations under attack… and for those of us that care about building a sustainable future… it could not have come at a worse time.

Labyrinth

The purpose of these texts is to highlight the dangers of static thinking in a dynamic world, but at this early stage we’re less interested in the particulars, those will come later, for now we’re more interested in filtering out a general-purpose framework which can be applied to practical effect. We’re not talking about superficial changes here, nor change for changes sake, instead, to give this aim a more concrete definition we use the term ‘contextual legitimacy’, or in application ‘contextual relevance’, both of which imply our focus is to make decisions based upon our perception of something external or greater (and which doesn’t necessarily mean in scale). This leads us to one of our fundamental maxims or beliefs, Architecture should always ‘speak’ of something larger than itself.

We highlight the term ‘speak’, because this correctly implies there should be a language at play, and for any language to be defined as such, this implies meaning, i.e. something to communicate, something that is greater than the sum of its parts. In this desire you could say we’re striving to throw a little something extra into the design mix outside of purely functional concerns, which sounds easy enough, but in application we’ve found there are inherent weaknesses in attempting to do so. For any language to function as such it must carry with it a bedrock of shared meaning (or at least be interpretable as such); a contextual approach requires the collective agreement that ‘symbols or forms’ are directly connected to the reality we all inhabit (something rarely seen in the construction world which mostly has differing priorities). As not all of us read our environment in the same way, this leads us to the problem our practice keeps running headlong into: what happens when you design to a context nobody recognises or wants to believe is the context at all?... or worse yet, when there are forces in the world specifically aiming at tearing any shared interpretation of our real context apart?

Over the last twenty years we’ve witnessed an acceleration of these forces. They are not new, they’ve always been there in one form or another but now are being unshackled, resourced and weaponised with intent. To adopt an appropriately Miltonian allegory, we find ourselves on a new battleground in a very ancient war… a war whose prize is the definition of reality itself. There is a terribly seductive power to Milton’s words ‘a mind is its own place’. When a mind can choose to believe whatever it wishes, preference a subjective reality over an objective one, what then happens to the state of nature we all must share? When reality is split into a hall of mirrors, reflecting endless distorted shards designed to confuse and disorient; when it becomes a wide dark sea without shore or lighthouse to reference ourselves against, how then do we chart a path back from the shadows projected to focus on the problems our society desperately needs us to? This is the edge our society has been tiptoeing along for quite some time now, teetering precariously alongside a seemingly endless void. Now however it feels like we’ve finally leapt, and everyone is racing to catch up with the implications of what that change means.

Now you may disagree with us here, but our concern has always been that architecture with its powerful language of permanence and authority, can inadvertently give legitimacy to these deceptions. To give a simple example, we all know there is a problem with sustainability, and yet continue pouring more concrete than ever to sustain the image of boundless resource and faux stability. There are immediate practicalities to this we could talk through, but the real question we want to ask here is why do this at all when we know it is so damaging to our future? It is the thought process behind these actions that interests us, because if you can somehow grapple with that, as a kernel so to speak, then there’s a chance you might also find a tool capable of altering the direction of travel.

For many of us, the built environment frames our world, all our interactions; we follow the routes it sets out mostly blissfully unaware of the thought processes behind them, the suggestions woven into each turn… when we compare this more designed reality to the differing reality a state of nature might provide us, it becomes hard to avoid drawing the conclusion that such abstract environments carry with them at least the potential, however small, to be influencing our decision making… in the case of a nature vs. abstraction argument, the discussion seems to boil down to observations over degrees of freedom and spatial potential (choice and the agency to do so) but there are far more sinister logics to be found here as we scratch away at the surface, and we do not think it wrong for Architects to be concerned about the wider implications of being surrounded by such narrowing abstraction day in, day out, over such vast scales of repetition… or indeed how such an environment might potentially be abused.

As we see it, this is the core of the problem; within such abstraction, the image has been granted a power it should never truly have, and has become a tool (or perhaps better a substitute) which can be wielded to terrifying effect by those with the reach and resources to do so. At the most superficial level it has resulted in a world where we tell ourselves we are all now part of some great machine, one that grants us no agency, no free will to change an outcome already written in stone. We elevated our market systems to near Godlike status, claiming they were the truth under which all must bow. The promise of freedom was its temptation, but in its pursuit we built for ourselves instead the perfect trap, a predestination of sorts, birthing a kind of faith in the process so tyrannical that to be found in any way critical or questioning of the underlying logic (or where that logic was headed) was to risk being branded a type of modern day heretic.

This is very much how it has felt to be one of those wanting to choose a more sustainable path, to be forced to climb an impossible mountain against unstoppable headwinds, and we should tell you it’s a pretty dark place to find yourself when stripped of any agency to influence the future, forced simply to watch as the world charges headlong in another direction entirely. For those of us sitting in that dark place however, the story told to us, the one repeated time and again that there is no alternative, has never really been anything more than that, a story, a convenient fiction. We are Architects after all, we have a set of skills that allow us to build whatever we might imagine, we see the world as clay, and we know any true interpretation of reality was torn apart a long time ago when we made the decision not to act, creating instead an alternate state where any defence of the status quo became implicitly an act of fatalism, everyone simply hoping something would appear to change the inevitable outcome instead of doing what they needed to do to change it… and in all truthfulness, for our part in that, Architects likely have little defence; the built environment plays a massive part in the problems we now face, and we do not think it unfair to say we’ve had little success in moving us toward safer trajectories. At this late stage all we can do now is be as honest as we can be about where we are and why, especially when that means acknowledging we are finding little in the current direction of travel that stands up to any serious interrogation... to quote the late Sir David Mackay, ‘we need a plan that adds up’.

If solutions are what we need, where do we start? Well, we might start with the past, with precedent, and there are certainly important lessons to be learned from doing so, to ground ourselves in an ever more turbulent world if nothing else; there are good reasons we turn to Milton as a reference for example, even after so many centuries… but we would caution there are hidden dangers in such an approach also. History can be seductive, can make things appear far simpler than they ever truly were, or imply patterns that were never truly patterns at all, and as far as we’re concerned it makes little sense for history to be the final authority when the challenges we face are in fact unprecedented. As we’ve touched on above and in our previous text, we find ourselves now caught in a terrible vice: the models and methods of the past are arguably those which have led us to our current precarious position. We look to them for stability often ignoring they were designed for completely different contexts, sometimes even completely different cultures, so to simply keep repeating them, however comfortable, would be to risk sidestepping the root causes of the problem entirely.

Consider the familiar path of modernity: chasing ever greater density, more concrete, more glass, more bricks, more steel, bigger mechanical systems, bigger populations, more energy use. All of us, implicitly or explicitly, are aware this model is now colliding head on with the hard reality of ecological overshoot, and to argue for its continuation based on perhaps economic feasibility or expediency is to knowingly choose ignorance over the true cost of its externalities, to run toward an easy wrong in place of a more difficult right. To proceed on such a path in the shadow of any genuine and forthright contextual analysis, to our mind, clearly flirts with madness… but we might also say exactly the same of returning to some imagined pastoral past. Our concern here is that there are simply too many of us now for our technology to fail, we are dependent upon it, and to entertain the notion we might comfortably slip back into some simpler mode of being would be to risk passively condemning a great many people to a great deal of suffering in order to get us there. This is something we cannot in our own minds justify.

What about looking to the future instead then? Absolutely, as long as expectations are kept measured, there’s a lot to be hopeful for as long as we’re willing to invest in it, but prudence also suggests relying on such things blindly would be an equally dangerous path. It is extremely unlikely that some magical one-stop-shop solution is going to appear to solve the myriad of problems we now have, there are simply too many, and any solutions we do put into practice are likely going to require significant investment to implement. Should we wait to see what comes before acting? In absolute certainty, no. There are some exceedingly clever people working hard on these problems, and most of us simply don’t have the skills or knowledge to, for example, mechanise the fusion of hydrogen or dissect the complexities of artificial photosynthesis, develop new nitrogen fixing crops or understand the chemical complexities of polymers which dissolve in seawater. Just because we aren’t doing these things ourselves however, doesn’t mean that our actions cannot help those who do. Our perspectives may differ but we all inhabit the same garden, and in any exploratory process there is one fundamentally precious component we can all help to contribute; time. Time to experiment with options, time to document and communicate, time to explore consequences, time to carefully think through complex problems and imagine new solutions. In the context of the discussions we have laid out above, this is now the only logical approach we can table which gives us any hope for a long term future. By finding ways to steer away from a frenetic race to the precipice all of us can help buy time for those working to find solutions, and in practical application this means every barrel of oil or litre of liquid gas we can avoid burning now, is in reality buying us all just that little bit of extra time to find and implement the solutions we need.

The present we are trying to create needs to be in some way a synthesis of all these overlapping arguments, and ‘buying time’ is the core theme we want to weave into whatever we choose to design going forward, it’s practical and actionable so is the key strategy we would ask all our clients to buy into, but alongside that we also need to recognise that our discussion has exposed a subtle change in our thinking, a secondary approach to consider. There are no certainties here for us anymore, we have stripped those illusions away, what remains now is better described as a discussion over probability, and how we tilt the scales to give us more favourable odds is the question we have instead implicitly started to ask… this is an idea we want to highlight here because within that change of mindset, there’s one last component we want to add to the mix, one last trick we have in our toolkit.

The problem with succumbing to fatalism, misplaced optimism or historicism is it robs us of one of the most powerful tools we can be using right now; the ability to communicate the urgency of our situation through the power of difference and distinction. We do not have all of the answers yet, we need to look for them, and every attempt at doing so holds within it the chance, however small, of unlocking further ideas that may lead us to new places, tilting the scales so to speak.

When architecture chooses to do something differently it doesn't just solve a problem; it also makes a statement. Partly, that in itself can signal that the old ways are no longer sufficient, but when the language adopted is also deliberately meaningful, it holds the power to reframe and communicate important concepts experientially, which is to say powerfully because you are physically redefining the context in which day to day decisions are made. Newton warned that reality responds to action, not intention. We do not need the continued manipulation of aesthetics as superficial compensation for ignoring the wider problems we should always have been solving, it makes little difference to us now what a building looks like in isolation. Instead we need something more complex, more integrated, where the act of forging an alternate path around unprecedented challenges can itself be both part of the message and the solution… and that… in brief… is the direction we’ve been attempting to turn.

Caesura

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the German writer and statesman, made a great observation. He said, ‘Architecture is frozen music’. We prefer to mostly avoid speculating over interpretation, but do think this is a slightly more nuanced concept than first appearances might suggest, perhaps worth thinking about. Properly decoding the ideas he was reaching toward would likely require a detailed conversation about the scientific understanding of the time, of harmonic sequences and whole number ratios, but our personal take on it coming from our comfortably modern perspective goes a lot further than this. We aren’t going to talk about that here, it would take too long and we suspect few would have the patience for it, we’ll come back to it later, but for now we will provocatively leave the words Fourier and Parallax on the table. Something to ponder over as we wander off in another direction entirely.

We want to tell you the story of a project we were involved in a great many years ago, a project which challenged fundamentally all of our assumptions about the built environment. To provide a little context, we’d recently achieved some small successes in the design of a school. The vogue at the time was for decorating schools with day-glo colours… to make them look trendy or some such justification, which always made little sense to us. Schools are a place of learning, they should be a celebration of all the astonishing ideas humanity has ever had, and in an ideal world we would ask that the core principles of those things should be communicated experientially in addition to being taught, carefully woven into the fabric of the design at every turn in a considered way (as to our mind, to do otherwise would be to miss the functional purpose of being a school). This gives a rich vein of design concepts to build around, and whilst we accept the expression ‘you can lead a horse to water’ does probably apply, call us crazy, we weren’t all that convinced painting something ‘hot pink’ automatically translated to better learning outcomes, no matter how cool that might be. It always seemed a little vapid in concept to us, and we could probably devote an entire thread to talking about the distinctions between induced vs. produced differences if we chose to critique it properly.

Within this project there was an idea we were toying with that we quite liked; we were trying to quantify the functional potential of a space… which… sounds completely insane when you say it out loud, but please bear with us. To explain, we were looking to find a spatial topology (types of layout) which contained the highest ‘potential’ to be adapted to serve as many functional roles as possible. There is a technical term we use for this in design called polyvalence, and it is deeply intertwined with the idea that sometimes, you can genuinely provide quantitatively more, by doing a lot less. This is an important idea in Architecture, but we don’t use it in quite the same way as some far greater Architects implied by using it. We eventually shifted to using the term entropy instead as this seemed a better fit to the idea of maximising or minimising the potential functional use, i.e. a measure of the number of overlapping states possible, and this definition was then built into our wider design work, as a unifying theme of sorts.

The next design opportunity we were afforded to re-engage with these ideas came with a simple housing project a couple of years later, this is the one we want to focus on here. We knew we wanted to bring the same concepts and the same language we used before into this project for consistency, but we also wanted to start overlapping a lot more deliberate meaning into what we were doing. It wasn’t enough to talk about the functional potential of space and its related concepts, these things were highly abstract, now we wanted our languages to do a little more direct heavy lifting. We’d not long gone through the summer of 2003 which was disturbingly hot and we were all acutely aware that the world was starting to change around us; so, being young and stupid, this was the challenge we decided to take on. How do we make our homes sustainable was the question we posed, and as a first stab in exploring the idea we adopted a mind-numbingly simple framework; whatever carbon we used in the building, in its construction, in its use, in food, in transport, etc.. we would look to the site around it to re-absorb. Brilliant! we thought to ourselves, we can imagine it like a set of scales, whenever we put weight on one side tipping the balance, we quickly need to run over and put some weight on the other side to maintain equilibrium. A nice simple archetypal reference, all actions having their equal and opposite.

We already knew the broad outline of the design language we were going to use, we were going to point sticks of carbon directly at the sky because we thought to ourselves ‘that’ll get the key message across’, i.e. building our language around things probably important to keep in mind as we go about our day to day lives, and you can find pictures of this in our gallery if you’re interested, a little out of the ordinary for a housing project perhaps and certainly not to everyone’s tastes, but fun and explorative nonetheless. At the time we felt it wasn’t really enough to use this one key defining gesture as only the message, seemed a bit obvious and justification for stepping away from convention demanded something with a little more depth, more layers of meaning to uncover, so we went back to our previous school design, picked up on the same theme of using foundational concepts in built form as an educational tool, and threw that at the site to see what would happen. What we ended up with was an array -complex or otherwise- of simple carbon rod gestures standing proudly across the site surrounding our dwellings, and importantly, as this implied a quantification of space, it led to the idea of trying to tie the size and perhaps even the density of this array directly to the areas of land we needed to reabsorb all the carbon dioxide we were expending, maybe with some nice trees and meadowland thrown in there to get the message across, i.e. an inescapable and visible built reminder of the literal impact we were having upon the world; not decoration, more a data visualisation you could walk through… and we loved it… right up until we started doing the basic numberwork.

It always amazes us how you can start in one place with a series of crazy ideas, and end up, by following the logic patiently and asking a few choice questions, in another place entirely. Imagine the situation; you’ve a nicely sized gently falling plot, nothing really noteworthy to add beyond it being beside a river with some existing mature trees, and an expectation placed upon you to organise roughly sixty homes or units on it. There’s nothing really out of the ordinary here, you see projects like this all across the country day in day out, but rather than providing sixty houses as you’re expected to… you instead table… six… maybe… if a couple of the families living there chose to be particularly frugal. We’re talking extremely low CO₂ dwellings here, far lower than most homes built even today… and then you push them underground because you realise you need the land area the buildings occupy themselves to make your numbers work… that was the reality our rough numberwork was implying… and it absolutely terrified us.

We refused to believe it, this is absurd we thought to ourselves, so we got our hands on a forty-kilometre slice of landscape survey data taken between the centre of the City of Exeter and a not particularly dense area of Dartmoor, and spent days counting the areas of trees and grassland vs. buildings, the idea being we could multiply this into a circle to give us a back-of-the-envelope ballpark estimate on where the whole city stood… it wasn’t even close, maybe fifteen percent of the CO₂ we were producing was being offset (by our rough numbers)… so we started looking nationally, a little over 25 million homes at that time (some 14 million of which were quite old stock and not all that efficient) and realised, we couldn’t say with any confidence we had enough land area in the UK to offset the CO₂ being produced by all these properties, and even if we removed them and replaced them all with high specification eco housing, we’d still be needing to cover nearly two thirds of the UK with dense forests and grassland… just for homes… no manufacture included, no services or offices included, no industry included, no shops and retail, just homes across 243,000km²… and this is how the scale of the problem opened up to us.

It is worth adding that we accept our process at the time was quite rudimentary. We are not climate scientists and did not have the benefit of some of the quite astonishing work that has been carried out over the years since, we had a paper from the American EPA on tree carbon sequestration produced back in the 90’s, and a couple of papers on meadowland figures we were using as our source material, all of which are nowhere close to the accuracy of modern data. We also weren’t drawing distinctions between sequestration rates and storage, had absolutely no idea at all about soil carbon sequestration, and disregarded farmland entirely (assuming the nitrate fertilisation of such would negate any carbon drawdown), these were the assumptions made and if we were to repeat the same study now we might find our numbers shifting, but doing so would miss the wider truth we’re trying to home in on here by relaying this story, the impact of this process did not come because we were reading it from some abstract text as you are now, after all, none of these ideas were new as such, they’d already been talked about in papers published by the wider climate and IPCC communities years before; what we’d done here though was to force them to become real at the scale of the individual, experientially, and we did this by working the problem through step by step and trying to find solutions, understanding that the questions being raised didn’t have satisfactory answers.

When the realisation dawns that for every sustainable home you build, you’re also needing to make allowances of space for circa sixty mature mixed species trees interspersed with meadowland, and then you cast an eye over all the densely built housing we’ve already built across the country, the practical scale of the challenge starts to hit home. This is the message we are trying to get across to you here, that there is a difference between knowing something exists, and working something out for yourself practically, between being aware of the tools, and wielding them with intent. There’s an experiential component to this problem that is important and easily missed, and which suggested to us that our built environment, i.e. the context in which we make decisions, wasn’t communicating the scale of the challenge we face in any meaningful way; rather it was hiding it. The model we had started to explore had inverted the age-old phrase ‘out of sight, out of mind’ to such an absurd degree, that it left us with nowhere to turn. It was the investment required to interpret that message in the first place that grounded the realisations and made them so terrifyingly real, and the question we’ve been asking ever since is how can we distil that idea, that more inductive philosophy into our design work to do exactly the same thing for others, to reveal the context and kick start a reappraisal of the situation. How do we make people aware that there are measurable consequences to whatever they now choose to do?

Needless to say, the concept went down like the Hindenburg and most others at the time thought we’d taken a step into insanity. You train as an Architect to design buildings after all, that is your reason for being, the more the better, to suddenly start -to all outward appearances- back pedalling against the flow is a very out of the ordinary thing to happen, made a lot of people uncomfortable... as we say though, there’s always at least some method within the madness, so that is where we want to take you next, to look at some of the other ideas we were playing with, all of which form a kind of soup that we like to swim around in.

The Translation of Syntax

We’re going to build on the ideas of the housing project later, but there’s a related bundle of topics we should probably address before doing so, to flesh out some wider influences for you so you can correctly interpret our imagery. We’ve used the word entropy multiple times now in slightly differing contexts; and have also used the terms probability and complexity… there exists a framework we can use to bring all these concepts together (and even time has its place to be found alongside them). When we think of entropy in vernacular we think of ageing or decay, but this is not a fair description of how we are using it here, we see entropy as the mechanism that gives the natural world the distinctive aesthetic it has, a pattern of potential which skirts the edge of chaos.

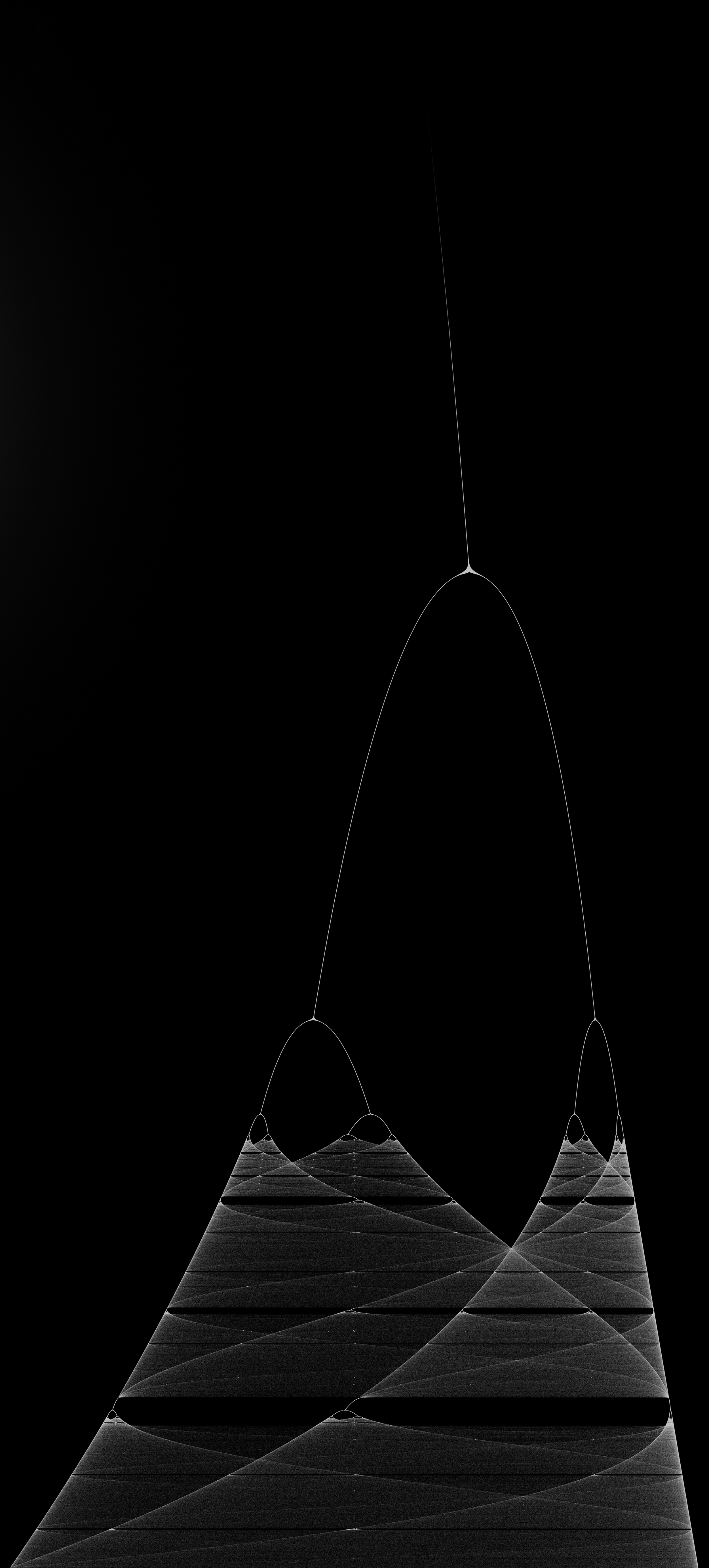

The physicist Murray Gell-Mann after being awarded his Nobel Prize turned his attention to a different puzzle, he sought a framework to better understand where complexity comes from. His measurement of complexity was revealed by the difficulty in describing something, and he proposed a conceptual model formed between two distinct poles to illustrate. Both poles in themselves were extremely simple drivers, both easy to define, but they existed as opposites to one another, two immiscible substances where complexity emerged on a scale drawn between them, represented as an arc. The greater the interaction between the two simple forces, the greater the emergent complexity and the harder things became to describe before sliding back down the scale into simplicity again. Entropy is the purest expression of this idea; a framework of high probabilistic vs. low probabilistic states in opposition which can be applied almost universally across any specific particular, and for Gell-Mann, it was the interaction between these states that created an environment within which interesting things began to appear.

[to interject on a slight tangent, you may be wondering why we’ve wandered off into such abstract physics and are concerned our doing so may come across as being a little intellectually superfluous. To explain, we recognise that -as set up right at the beginning of this discussion- we, as a practice, are trying to stand in two logically contradictory positions at the same time almost like we’re having our cake and trying to eat it. Here what we’re trying to explore with you is a framework which explains ‘the why’ of choosing such a position. For Gell-Mann, much as for people such as Gödel, certain logical approaches can be double edged swords, can have both positive and negative traits depending on the context in which they are applied, and there are always those times when following one logical approach exclusively may leave you going around in circles. By holding two contradictory states in hand at the same time, you provide yourself with a ready pathway out of any logical trap you might find yourself within, you can flux and weave your way to a solution backwards and forwards rather than finding yourself painted into a corner, and this is why we’re bringing such a complex idea to the table, it provides the necessary framework to understand why we adopt the position we do].

When we think about a practical analogy for this idea that is easily communicable, our mind turns to the familiar states of matter we all know well; we imagine the simplicity of absolute order to be akin to something frozen, very low energy, unchanging and solid, and we imagine the opposing absolute chaos to be akin to a gas or plasma, hot and unruly, constantly on the move. Complexity for us lies between these two opposites in what logically would be described as a more fluidic state, propagating as ripples and waves, interference and destruction, constantly shifting form based on the shape of its surroundings, i.e. contextually responsive. This influences a lot of the references we carefully choose or languages we might adopt, being revealed in foundational ideas such as those we quoted from Heraclitus right back at the start of this journey, or even in far older imagery we might playfully bring to the table, the wellspring, the house of waters, the pool of two truths, or an earthbound ocean amongst a great heavenly sea.

This relationship between the goal of complexity and our drive toward simplicity can be problematic though. We find ourselves continually pulled in opposing directions, wanting things to be simple, but not simplistic, and those are not the same thing at all. When you follow the above framework through to logical conclusions, what you begin to realise is that sometimes, things that may appear complex on the surface, actually turn out to be surprisingly simple, and conversely, things that might appear superficially simple, actually turn out to be far more complex. The best answer we can give as to why that might be the case boils down to a thing’s relationship with its context, i.e. how those two things, object and context interact. Let us give a practical example; as precedent, we are influenced strongly by mid-century Literalism, this is a movement which appeared mostly in the arts, in sculpture and painting, and again, in the vernacular, you might know it by another name; Minimalism. We prefer not to use that definition however, it has been abused greatly, especially within architecture and design. The term does not fully capture what these artists were trying to do.

The distinction is a subtle one; Literalism (to be literal), is not simply Reductivism (to reduce), that on its own becomes something else entirely, vacuous and shallow, valuing only the self-referential and obsessive image of itself. Starting instead as a reaction against the objectifying and anti-contextual logic of the gallery space, the goal of Literalism was to strip away the symbolic, strip away the illusions in order to expose deeper truths, redefining its own language in the process in orientation toward things that could be said to be universal or inescapably true. The by-product of this process was honesty, and the message each piece or painting sought to communicate became a more complex beast than the immediacy of whatever superficial form it chose to adopt, becoming instead a mechanism toward the understanding of something, not simply the obsession over a static end result.

As the language matured the works began to push further toward the site-specific, tearing down the traditional barriers that separated a form from its context. Rosalind Krauss described this process well, moving from ‘a thing isolated’ to become landscape, and building, and sculpture all at once, demanding instead a reframing of perception from its audience to focus not on the immediacy of the object itself, but rather beyond it, to the reality a piece found itself within… and so extreme this process became, that over time it started resembling something else entirely, something far older, bearing a disturbing similarity to processes almost foundationally empirical in intent, to arguments written down by authors such as Bacon so many years before. In application, in praxis so to speak, it even carried a similar intent, seemingly repeated again and again across time… its own Miltonian rebellion against the symbolic deceptions of its age.

Literalism orients itself outwards, not inwards, that is the clearest distinction we can make, it cannot exist without a context in which to ground it, and via this intentional relationship creates for itself its own arc of complexity, the simplicity of the object vs. the simplicity of everything else, the point vs. a cosine circle of infinite states that surround it, where any meaning we might wish to convey sits somewhere between, within a more complex interpretive envelope. In language, it seeks to be honest about what it reveals and we value this trait immensely, find it relevant within our wider discussions which is why we bring it to the table, but this search for an honest aesthetic through near empirical rigour is not the only path we can take to achieve a similar goal; a parallel path can also be found within the Japanese philosophy of Wabi Sabi.

Where Literalism arrives through a process of analytical reduction and process, Wabi Sabi reaches a similar destination by embracing the natural world’s own logic, celebrating its own interpretation of entropic complexity by finding beauty in impermanence and imperfection. In short, it introduces the concept of time… but time as a language is a topic best left to a future post, there are implications to this idea which need more space than we have here to unfold into. In its absence we would direct your attention instead to other brief observations of Wabi Sabi we find relevant. There is a practical streak we enjoy here; the idea of valuing what we already have, of repairing something broken not merely to fix it but to celebrate its history (as in the process of Kintsugi) is a deeply relevant gesture in an otherwise throwaway society; and the focus on natural materials, upon restraint, we see as a practical, lower-energy approach to living that offers much of value within the wider arguments we’ve already talked through. You may be surprised to hear that most of the work our practice completes is a far stretch from the super modern literalist images we might show you in our gallery, most of it is actually to historic and listed buildings, and we see no contradiction in that. It appeals to the Wabi Sabi side of us to protect and repair, and there is an honest humility in that process which is an important component of who we choose to be as Architects.

Where we diverge from Wabi Sabi is in the observation that whilst the language is highly considered and evolved, the underpinning foundation upon which it builds itself leans more toward the instinctive than measured. All representations are in some way symbolic, you cannot fully escape that, but not all symbols are the same, some are more useful than others. Whilst we’d agree Wabi Sabi does indeed speak outwardly, it does not specifically do so with the tools necessary to more deeply interrogate the references it ties itself to, often skirting close, but never quite reaching that same intent. To our minds, the ability to measure (even if you choose not to) is important. It is a foundational skill handed from one generation to the next and was the key ‘big idea’ we wanted you to take away from the underground housing project we tabled previously, that measuring something (even if only as experiential representation) is important because without it we can have no objective measure of reality to share between us, this is the criticism we level at current architectural discourse. When we imagine a world where those mechanisms have been stripped away in preference for other things, we imagine an environment in which we’d have little awareness of wider climate changes at all, or biodiversity loss, or sea-ice change, or inequality, or any of the other slow gradual changes that have crept up on us over the past few decades… these changes would become abstract, not literal, perhaps even easily dismissed… and this worries us… it sounds disturbingly close to a kind of new dark age that Bacon worked so hard to push us away from, and we’re not fully convinced that would be an appropriate direction to keep leading people given the challenges we face. If our wider argument is over one of probabilities, and our intent is to find ways to ‘tilt the scales’ in our favour, finding ways to distribute these tools as widely as possible seems a far more contextually appropriate strategy than pretending they simply don’t exist.

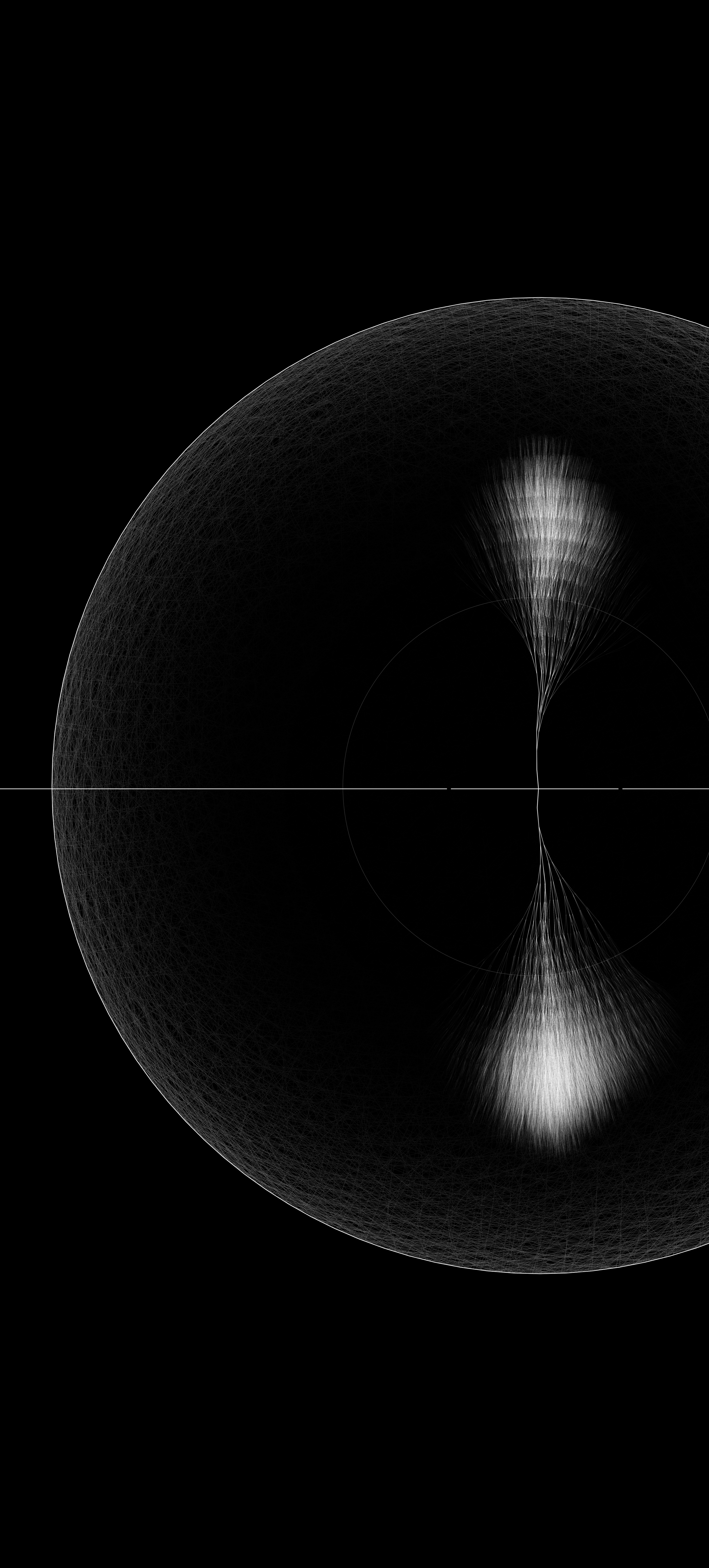

This is an idea we’re still playing with and are unsure of how best to implement. On the surface, it implies we should be pulling apart the ideas of Wabi Sabi to isolate out the parts we don’t want and rebuild the parts we do on top of a different foundation. To illustrate one such possible approach we could table the Zero One concept project you’ll find in the gallery. Here we chose to directly take the work of Newton [The Rotation of Fluids from Principia, another quiet liquid reference], and rebuild it as a three dimensional form, trying to find ways to overlap as many subtle meanings as possible whilst also keeping the overall form simple. There are nods to calculus, to pi, to two fundamental states, a ground [literally] and a positive, ascent and descent, spatial transformation and rotation, all unified by the ideas we’ve been speaking about above, i.e. the arc of complexity… but the result we find surprisingly serene, quite gentle in its ripples and implied reflections. We don’t like that it stands isolated from any direct context, that doesn’t seem to fit, but otherwise it very much does seem to capture many of the things we’re trying to weave together in the fusing of these differing languages, and -at some level- it appeals to us to use ideas that are hundreds of years old taken from one of our greatest minds in such a way. There is a timeless universal quality to these things, underpinned by quiet geometry and making statements which hint at wider truths to find should you wish to look for them. On the outside, you might think Newton a strange reference to make within a wider Architectural setting, but when you consider that pretty much every single building all across the modern world has been built directly on the back of the work he completed, the importance of the connection we are drawing hopefully becomes a little clearer for you. If you want a candidate for a true universal language to all Architecture, this is likely one of the few common threads you’ll find that unifies them all… we just don’t normally think about his work in quite this way.

Where else do we diverge from Wabi Sabi? We’re deeply uncomfortable with the idea that we can simply adopt a language wholesale from somewhere else (Japan in this case) without consequence. Our cultures are fundamentally different, we even structure our spoken languages differently, and probably nowhere are the cultural differences more readily observed than in how we manipulate space: The Japanese have a spatial language built around the use of the floor whereas in the West we have a spatial language built around the use of the wall… it’s an observation we often play with.

We like complex planes; they are an important foundational concept in understanding the world around us. Sitting as the interpretive gateway between three wider quantitative languages -even some imaginary ones- they carry the potential to translate the immediate specific geometry of architecture into explorations of far more complex ideas. We use them a great deal, a suggestive motif if you will, but would ask that you step back and look at these gestures in a slightly different way. They are not simply stylistic decisions as perhaps a choice over what type of wallpaper to use, they are instead deeply intertwined with this idea of overlapping functional states (entropy as discussed previously) where the broad idea is to create tools that prescribe less and imply more, becoming both complex and simple at the same time. Instead of giving you -as a quick example- ‘a shelf’ to inhabit as a design solution, we prefer instead to give you the potential for all possible shelf positions at the same time, which is to see design not as a static object but rather in a state of superposition for want of a better term. Simply slot in or over whatever component or form you wish to inhabit and change it everyday should the preference take you… draw pictures with it, count things on it, do nothing at all… whatever feels appropriate to your needs. Design when it becomes too focused on a single end goal runs the risk of becoming deeply prescriptive, glacially tied to one interpretation of how the world should be. It might provide a more superficially stable or comfortable state and we’d agree the compositions can be quite beautiful, but they’re also quantitatively less useful, less adaptive to changing needs, and as this broader idea of change over time is something we’re trying to embody, it makes sense for us to adopt a different approach to reveal it.

We see playing with gestures like this as pushing the other way from simply ‘the frozen object’, becoming fuzzier, less defined, and providing us a route past the implicit contradiction of wanting buildings to become more fluid without literally making them from fluids (an idea that does not make for happy Structural Engineers). This is not simply about creating the representation of fluidity in a superficially ‘wavy’ way, instead these gestures celebrate being almost the total inverse, not appearing fluidic at all, but being fluidic in function, that is the target we aim for. The message is not intended to be about what something is, but rather about what it is doing, that is the shift in perspective they require; they are mechanisms to embody actual change, not abstract representations of change, and by doing so reveal themselves to be small microcosms of the wider macroscopic site scale logics we try to reach toward, operating over multiple scales at once almost like a fractal. How do we make spaces more adaptable is a question we find highly contextually relevant, and there’s also a strange kind of freedom hidden away behind that idea, in the idea of impermanence and agency in how our environment is organised. These ideas we feel carry an important message, though admittedly, in an implicit way that has proven easy to misinterpret.

[Again, to interject and clarify, we’re not suggesting there’s no place for the more instinctive approaches of Wabi Sabi. The instinctive is not necessarily always wrong, quick and dirty can often be a useful tool, and if nothing else can add a layer of interference that mixes things up a bit, there is an artistic side to the design of buildings after all which is important not to dismiss (as per Vitruvius’ famous trinity). Einstein warned ‘not everything that counts can be counted’ which we agree with, and the last thing we’d want for society is the creation of millions of Arnold Rimmer’s alphabetising their sock drawers ad absurdum. The key here seems to be in finding just the right balance, the potential for (within degrees of freedom), rather than by the diktat of, and as a reference we’d probably cite Jun'ichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows if you want to delve a little more rigorously into the ideas we’re chasing].

This leads us to the end of this current section, and here we want to briefly address the nagging question of why consider any of this at all? Does such a collection of deeply nuanced concepts carry any merit in the world we now inhabit? In a progressively more authoritarian, anti-science, post-truth world of wilful illusion and shadow we’re spiralling toward?… we’d argue that they do, they are a palette specifically chosen to do exactly that, our direct and considered response to what we’re seeing happen to the world. As we’ve said before, none of the forces we are seeing are new, sliding as they are down the scale into far simpler states of being. If the symbols we use no longer carry meaning, or that meaning has been corrupted, then we need to find new ways to communicate… that is what we’re trying to explore here, and we’re hoping by this point with these final few brief observations that we’ve now given you enough of a framework to start seeing how a sweeping collection of maddeningly disparate parts and images are beginning to coalesce together into a more satisfying and complete whole, all woven carefully to form a grounded contextually relevant argument. The method within the madness so to speak.

Next we need to speak about how all this is applied, and what real world impact it has on the buildings we design, and we also need to talk about the language of time... because, well… that should be mildly interesting.

…to be continued.